The EU Commission’s proposals to simplify parts of the EU’s digital regulation framework have had a mixed, but generally positive, reaction from business. Civil society has reacted less well with Max Schrems describing it as “the biggest attack on European’s digital rights in years”.

We look behind the hyperbole to consider what the reforms do in practice and what this means for digital competitiveness in the EU.

The EU Digital Package

The reforms are made up of two key instruments, the Digital Omnibus (2025/0360 (COD)) and the Digital Omnibus on AI (2025/0359 (COD)).

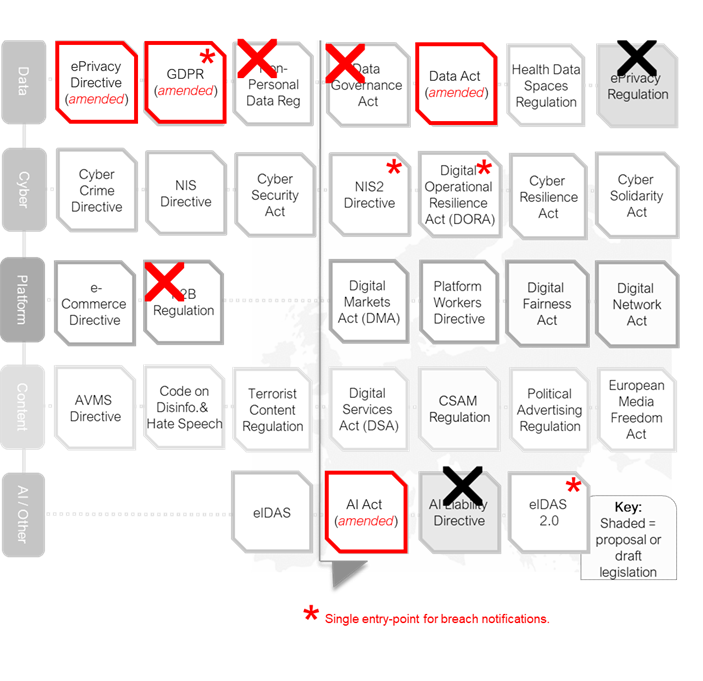

Together, they make significant changes to the so-called EU Digital Package. This is made up of different but interconnected instruments, identified by a whirl of different acronyms such as the DSA, the DGA, NIS2, DORA and so on. More details are in our EU Digital Handbook.

The Digital Omnibus amends and consolidates some of those instruments, and repeals others. The diagram below shows the effect of these changes in red.

Key changes in relation to AI

Some of the key proposals are in relation to artificial intelligence. The much-maligned EU AI Act, most of which is yet to come into force, will be further amended. There are a number of changes but the most notable are to:

Remove AI literacy obligations. These obligations on providers and deployers to ensure the AI literacy of their staff, which came into force earlier this year, will be replaced by soft obligations on Commission and Member States to encourage AI literacy.

Delay rules for “high risk” systems. The implementation dates for the rules on “high-risk” systems are pushed back. The position here is complex, but the rules should not apply until December 2027. This extends to August 2028 in the case of Annex 1 systems (such as medical devices or radio equipment) or even 2030 if used by public authorities.

Exemptions for mid-caps. Similarly, the exceptions for small and medium-sized enterprises are extended to also apply to small mid-cap companies (i.e. companies with fewer than 750 employees and an annual turnover of less than €150m).

Alongside the changes to the EU AI Act are complementary changes to the GDPR to address the difficult questions about the legal basis for the training of AI systems on content from the internet.

The first recognises that the legitimate interests legal basis (Article 6(1)(f)) will presumptively apply to the development and operation of AI systems unless those interests are overridden by the rights and freedoms of data subjects. This is subject to safeguards including measures to minimise the amount of personal data and to give data subjects enhanced opt-out rights.

The second is to create a new legal basis for the processing of special category personal data for the development and operation of AI systems (new Article 9(2)(k)). Without this change, the training of AI systems is extremely hard to reconcile with the requirements of the GDPR given the broad definition of special category personal data and its miscibility with “normal” personal data. This again is subject to safeguards, including avoiding and removing special category personal data where possible and, if not, taking measures to prevent it being disclosed. Whether Grok can still tell you “Joe Biden is a Democrat”, remains to be seen.

Key changes under the GDPR

The changes to the GDPR to enable AI training are accompanied by a number of other modest reforms. They include:

Protection against “abusive” requests: There will be additional protection for controllers who are subject to subject access requests that are abusive – i.e. not for purposes of protection of personal data. This may be a reaction to the AG’s opinion in Brillen Rottler (C‑526/24) that suggests a very high bar for controllers to show a request is abusive, even in the context of requests made deliberately to provoke a compensation claim. In practice this protection should be easy to evade by careful formulation of the request; it is notable that it does not go as far as the recent UK reforms on subject access.

Extending breach notification: The time to notify a breach will extend to a weekend-protecting 96 hours. It will also be possible to use the single-entry breach notification tool.

Codify SRB approach to personal data: This applies a “relative” approach to identification when considering what is/is not personal data. The risk of identification is based on the information available to a person (and not other information that is not available to that person). This codifies the approach in EDPS v SRB (C-413/23 P), but has not been well received. Max Schrems describes it as “like a gun law that only applies to guns when the owner confirms he … intends to shoot someone”.

A common DPIA list: The EDPB is to draw up a common list of processing that is likely to require a data protection impact assessment. This will be a significant improvement to the current situation in which each supervisory authority has their own list. Whether the final list delivers simplification or is just a superset of those individual lists remains to be seen…

It is interesting to think about what is not included. An obvious omission is any reforms to the rules of transborder dataflow. These have been almost universally criticised by business as being unworkable – particularly the costly and expensive process of assessing foreign laws to complete a transfer impact assessment. However, no relief is offered.

The cookie provisions in the ePrivacy Directive – so far as they apply to personal data – will also be transferred to the GDPR with new exceptions for analytics and security use cases. These changes will also require controllers to respect machine-based browser instructions to consent (or not) to cookies. These rules do not apply to media service providers. The intention is these browser-based signals will eventually remove the need for cookie banners.

Other changes

Beyond the AI and GDPR related changes are a host of other simplification proposals. These include:

A single-entry point for data protection notifications: There will be a single-entry point for breach notifications under GDPR, NIS2, eIDAS2, DORA and the Critical Entities Resilience Directive. This is very welcome.

Repeal and consolidation: The P2B Regulation, Non-Personal Data Regulation and Data Governance Act and Open Data Directive will all be repealed. Parts of the latter instruments will be incorporated into the Data Act to consolidate most “data” regulation in one place (though the European Health Data Spaces Regulation remains separate). Whether some of the more exotic provisions, such as the framework on data altruism, will have greater impact in the Data Act remains to be seen.

Cloud switching: The rules on cloud switching will be slightly relaxed, for example in relation to pre-existing contracts for bespoke cloud offerings.

EU competitiveness and the road ahead

The underlying rationale of the Commission is “drive to simplify, clarify and improve the EU acquis, as a key measure to support the EU’s competitiveness”. After all, if AI is the fourth industrial revolution, there are significant strategic and economic risks for the EU if that technology is controlled by entities in the US or China.

The EU Commission clearly sees simplification (also known as “deregulation”) as the route to creating a digital EU champion. However, the changes in the Omnibuses are modest and hardly leave the EU with a simple or streamlined framework.

There is also stiff opposition. Some of that is based on fundamental rights; but some arises from different visions for the EU’s digital single market. In Max Schrems’ words, the changes have “no benefits for European SMEs – but opening the flood gates for the ‘big guys’”. In other words, some in the EU see the solution as not competing globally, but rather tilting the playing field to allow smaller EU companies to win in the EU.

This feels like an “Amish” approach to regulation. The EU could build increasingly strong regulatory barriers to protect it from the intense tide of technological change, but it risks becoming a backwater. That is not always a bad thing. The Amish’s simple and agrarian lifestyle eschews modern technologies, but provides that community with fulfilling lives and low levels of depression and anxiety. Stepping off the digital escalator likely does have advantages, but given the current geo-political pressures this may not be workable for one of the world’s major power blocks.

These reforms have some way to go and risk upsetting everyone. Those wanting simplification will welcome the changes, but they are already modest – save perhaps the GDPR changes for AI training – and are likely to get watered down further (or worse have new requirements bolted on).

The consultation on these proposals is open until 23 January 2026 (here).

The Digital Omnibus (2025/0360 (COD)) is here.

The Digital Omnibus on AI (2025/0359 (COD)) is here.

/Passle/5c4b4157989b6f1634166cf2/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-01-28-11-42-24-951-6979f620da2c44bd51323e05.jpg)

/Passle/5c4b4157989b6f1634166cf2/SearchServiceImages/2026-02-12-13-12-38-049-698dd1c64d2faa8c1a88c2ed.jpg)

/Passle/5c4b4157989b6f1634166cf2/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-02-10-09-26-10-525-698af9b2b876970f0dcaea7f.jpg)